Two-fifths of a tennis court. About six car park spaces. Three-tenths of an IMAX screen.

That’s the size of my front yard. Yet despite its limited expanse, and its densely urban situation 10 km north of Melbourne CBD, my yard is habitat for at least five species of native bees.

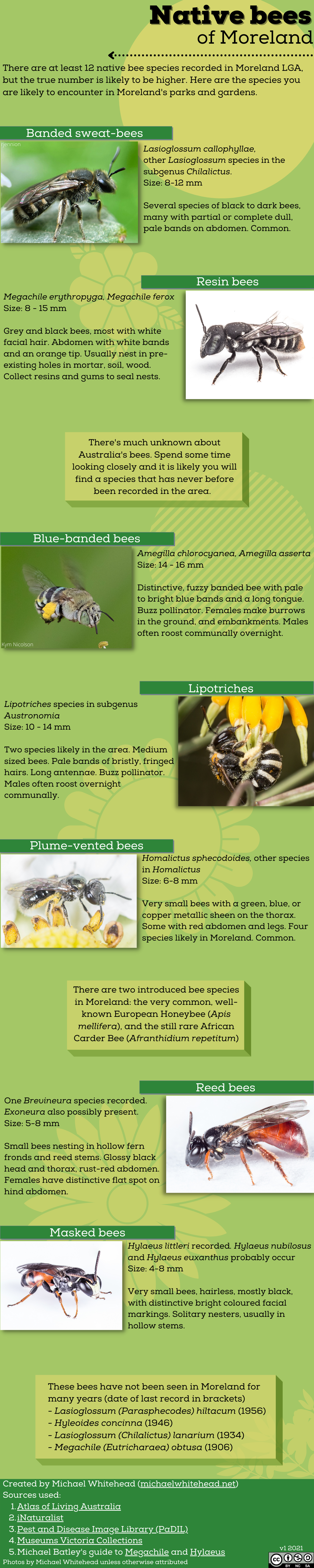

I began watching the bees closely last year in lockdown. The tiny, faintly metallic Sweat Bees (Homalictus) are most common. They appear first in Spring, visiting the Wahlenbergia, the Oxalis weed in the lawn, the strawberry, and rocket flowers; anywhere there’s pollen.

Later, the bold and stripey Lipotriches turn up. Like rock-climbers gripping an overhang, they lock themselves upside down to the anthers of dangling Dianella flowers, emitting short zip-like buzzes as they work with methodical focus.

Then when Summer days begin to blaze, the hyperactive Resin Bees (Megachile) arrive, with that distinctive ember thumb print on their behinds. They fire around the yard like deranged bullets, collecting pollen and scouting for cracks to nest in.

That such biodiversity endures in this landscape—once grassy woodland, now houses, roads, and light industrial—is a testament to these species’ resilience. But their persistence also begs the question of which species might now be absent, less tolerant of such drastic change.

The White-headed Digger Bee (Amegilla albiceps) is one such bee. Large, rotund, and covered in a pelt of golden and white fuzz, one has not been recorded in Melbourne for at least 70 years, perhaps longer. In a Summer free of travel restrictions, I’ll leave town to seek the White-headed Digger. But for now, I’ll keep discovering the delightful locals. It’s Homalictus season now.

This mini essay was originally written for the Urban Field Naturalist Project